In September 2018, a special investigation team of the Karnataka police identified Parashuram Waghmare as one of the alleged killers of journalist Gauri Lankesh, who was shot dead in 2017 at her Bengaluru residence. The lead came through the examination of the walking pattern of the killers as captured in the CCTV footage at the time of the murder. The Directorate of Forensic Sciences in Gujarat, which was working with the police on the investigation, used a technique called forensic gait analysis to match the walking pattern of the killers with that of the suspects.

Forensic gait analysis is based on the premise that every individual’s walking pattern is unique. It comes in handy to identify a person in cases where the CCTV camera has captured the act of the crime but couldn’t capture the face of the perpetrator due to poor lighting, the position of the camera, or because the face was covered with a mask or cloth. The technique was first admitted as evidence by a London court in a murder case in 2000. The perpetrator caught on CCTV footage had a bow-legged gait matching one of the suspects, which according to the gait expert who offered testimony during the trial was found in only 5% of the country’s population.

During gait analysis, the walking style of the perpetrator from the CCTV footage is examined to generate a pattern called gait signature. It is then compared with the gait signature generated from a second footage of suspects, which can be from a CCTV footage captured before or after the crime or a re-enactment of it by law enforcement agencies during the investigation as was done in Gauri Lankesh murder investigation. Gait signature is drawn from combination elements such as the posture of the body while walking; hand swing; the position of head, neck and shoulder; knee-flexion during stance; distance between the steps; angle of feet; pelvic rotation and weight distribution.

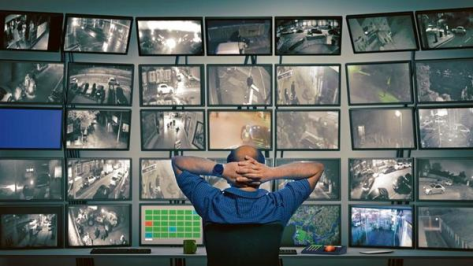

If done right, forensic gait analysis could possibly revolutionize policing in ways similar to the impact that fingerprint analysis had on the field in the early 20th century. Crime solving is all about matching the remnants of a scene to the person who might have been there. While a fingerprint or hair or blood are clear markers of identity, the way someone walks could be as unique and integral to identity. And in an age where cameras are coming up everywhere, making sense of all the hours of stored footage is where the next big policing breakthrough is likely to come from.

Gait analysis can be done manually by carefully examining every frame of the footage and then drawing a conclusion based entirely on observations. The other and considerably more reliable approach is the computer vision approach, which uses specially designed algorithms to determine a person’s gait from a video footage and then compares the gait pattern of the perpetrator with that of the suspect. This approach uses software tools to measure lengths or angles of the limbs during movements across each frame.

While gait analysis has been used as supportive evidence in the UK and the Netherlands, its use for forensic purposes has been limited or non-existential elsewhere. However, authorities across the world are now showing increasing interest. China which has one of the largest CCTV networks in the world, with 170 million cameras across the country, is using a new surveillance system developed by the Chinese AI startup Watrix, which can identify individuals from a distance of 50 meters based purely on the shape of their body and style of walk.

Experts, however, believe that gait analysis is still at a very nascent stage and more research is required to attain results which are more precise.

A joint team of researchers from the Netherlands Forensic Institute, in a paper published in Forensic Sciences Research in February 2018, acknowledge the veracity of gait analysis but also argues that humans can adjust their gait according to circumstances. It also claims that the quality of the footage, frame rates, and the lack of solid scientific knowledgebase about intra and inter-subject variability in gait features can affect the analysis.

In gait we trust

However, there are studies which suggest that a careful examination of the walking style of a suspect with that of the criminal in the CCTV footage by skilled observers can nudge authorities in the right direction. One such study was carried out by a leading British forensic gait analyst, Ivan Birch, in 2013. Published in the Science and Justice Journal, the study hired seven gait analysts and asked them to examine five CCTV samples, where each sample showed a target walker and five suspect walkers, to determine which of the suspect walkers was the target walker. All the walkers were wearing identical loose-fitting clothing to mask their body contours and had their faces covered. At the end of the study, the analysts correctly identified the suspect walker in 71% of the cases. However, it was also found that correct decisions were higher in cases where the footage of the target walker and that of the suspect walker were captured from the same angle by the CCTV camera.

A major limitation of forensic gait analysis is the fact that it often requires interpretation of research that has been conducted under controlled environments through clinical gait analysis, claims a joint report by the Royal Society of Scotland and the Judicial College published in November 2017.

It argues that unlike forensic gait analysis, clinical gait analysis is more planned and organized, with multiple cameras and sophisticated equipment to capture every little detail related to a person’s gait in order to carry out three-dimensional measurements. Whereas, in forensic gait analysis, experts often have to rely on CCTV camera footage which may not always be in the ideal position or may be marred by poor lighting or camera quality, often resulting in angles being estimated from a two-dimensional video.

Then, there is the question of how unique is a person’s gait. Studies have shown that a person’ gait may vary based on the person’s speed, the crowding on the street, the nature of the surface, the time of the day, physical conditions, footwear, and the amount of alcohol he/she has had.

The Indian scenario

As far as laws in India are concerned, “any kind of evidence in electronic format is admissible in courts, under section 65A of the Indian Evidence Act," points out advocate Pavan Duggal. However, if the analysis is based on the interpretation of an expert witness, some sort of technical qualification or training will have to be produced. Self-proclaimed experts won’t suffice, adds Duggal.

“Gait analysis is an expert opinion as per the Indian Evidence Act and admissible as evidence. The analysis in the Gauri Lankesh case was made by an expert from the Directorate of Forensic Science, Gujarat. DFS is certified u/s 79-A of IT Act as an Examiner of Electronic Evidence. In the eyes of law, they are treated as an expert," says DCP M.N. Anuchet, the chief investigating officer in the Gauri Lankesh murder case.

Beyond the realm of gait itself, law enforcement agencies are increasingly turning to technology during an investigation. While technologies like Mobile Signal Triangulation which can pinpoint a suspect’s location at the time of crime based on cellphone call records have begun to be deployed on a regular basis, newer tools like gait analysis, AI-backed face recognition, or machine learning tools to predict violent behaviour by a crowd are slowly gaining acceptance.

Delhi Police recently announced plans to use cutting-edge technology in investigations and has roped in the Indraprastha Institute of Technology Delhi (IIIT-D) for assistance. The institute has set up a Centre for Technology and Policing, “which will help Delhi Police by providing them with the latest tools for interrogation, surveillance, and tracking along with research assistance in the field of biometrics, image processing, and forensic science," said Ranjan Bose, director, IIIT-D.

Advances in technology will also cut down the time spent on long-winded processes, which impedes investigative swiftness.

A case in point is the use of a Rapid DNA machine by the Bensalem police department in Philadelphia in the US. It can analyze DNA samples and give results in 90 minutes, unlike accredited labs which handle multiple forensic DNA analyses and take days to give results. These machines are as big as a desktop PC, which makes installing them easy, and can be operated by the police officials themselves. They use a cartridge, which costs $150, for every DNA analysis. Permitted by the US government, the machines will be installed in more police stations across the country. These machines can come in very handy in a country like India where the lack of DNA testing infrastructure and manpower has led to a serious backlog of unexamined DNA samples.

According to the Directorate of Forensic Science Services (DFSS) data, DNA samples from 12,072 sexual assault cases were waiting for examination in three of the six central forensic science laboratories which had the facility to test the samples, as on December 2017.

AI is helping too

Machine learning is also being used now to assist in policing. Students at IIT Madras, for instance, have developed an AI-based crowd analysis tool which uses action recognition algorithms, crowd density maps, and analysis of live images captured by CCTV cameras to predict violent behaviour like stone pelting. The tool was showcased at Army Technology Seminar 2019 in Delhi by the IIT students.

Another AI-driven initiative in this area has come from a Gurgaon-based startup Staqu. The company has been working with several state police departments. One of their solutions, called Smart Glass, which is in pilot stage, uses facial recognition tools to auto-scan the faces and look up in a database for probable matches. The ability to faces via the Trinetra app has already come in handy to bust criminal gangs in UP. “Staqu’s platform has not only helped us build a centralized database which includes the photos and history of all the criminals who are in and out of prison but has also made our operations much easier. Within seconds, we can verify if a person has a criminal record or not," says SK Bhagat, IG, Lucknow range. Staqu’s solutions have been used by Rajasthan, Punjab, Uttarakhand and the UP police to solve over 1,500 cases and build a database of more than 80,000 criminals.

Even though these technologies are fairly young and require much more research, they offer a window into the future of law enforcement. And it is a future where the emerging new concerns of privacy and the right to be left alone will co-exist with the reality of an increasingly monitored world.

Posted on :

Feb 04, 2019